Katyń – rocznica w lesie umarłych / KATYN: THE 79th Anniversary of the Forest of Death

- 03/31/2019 05:15 PM

Kwiecień 1940 roku to miesiąc, w którym w lesie katyńskim zamordowanych zostały tysiące Polaków. Na całym świecie Polacy próbują zachować pamięć o tych wydarzeniach. Ja także myślałem ostatnio o Katyniu. Myślałem o Katyniu i o moim ojcu.

Kiedy byłem dzieckiem, mój ojciec często opowiadał mi historie z czasów wojny. O tym, co stało się z jego rodziną, z rodziną mamy, z Polską. Do jednej z historii powracał bardzo często, do tego, co wydarzyło się w 1940 roku w Lesie Katyńskim, niedaleko od rosyjskiego Smoleńska. Ojciec mówił mi, że Rosjanie zawieźli tam i zamordowali 15-20 tysięcy polskich oficerów. Że nikt nie wie dokładnie, ilu ich tam zginęło.

Ojciec powtarzał: „Trudno jest zliczyć kości”.

Oficerowie, którzy zostali zamordowani, byli w większości rezerwistami. Na co dzień byli lekarzami i prawnikami, nauczycielami i księżmi. Mój ojciec powtarzał, że byli przyszłością Polski. Mówił, że Rosjanie nie chcieli, aby Polskę czekała przyszłość, więc zgromadzili w lesie lekarzy i prawników, naukowców i bibliotekarzy; związali ich, zawiązali im oczy opaskami, po czym strzelali im w tył głowy. Pochowali ich w masowych mogiłach.

Ojciec też mówił mi, że ludzie wiedzieli o tym, co tam się stało. O Katyniu wiedziały inne państwa, takie jak USA czy Wielka Brytania, ale nikt niczego z tym nie zrobił. Rosjanie, co jest oczywiste, zaprzeczyli swojemu sprawstwu, a inne kraje nie chciały się do sprawy mieszać. Nie chciały o tym mówić, zupełnie jakby nie było sensu mówić głośno o masakrze i ludobójstwie.

Mój ojciec nigdy nie zapomniał o Katyniu i nie chciał, abym ja kiedykolwiek zapomniał.

Lata temu napisałem o Katyniu wiersz, który znalazł się w tomie „Echoes of Tattered Tongues” – zbiorze wierszy o wojennych doświadczeniach moich rodziców. Z okazji nadchodzącej 79. rocznicy Zbrodni Katyńskiej, chciałbym się nim z Wami podzielić.

Katyń

Tutaj nie ma Chińskiego Muru

Żadnych przechylających się lub nieprzechylających wież

Obwieszczających sukces jakiegoś króla

Lub kpiących z porażki innego

Nie ma lśniących katedr, w których możesz

Modlić się o przebaczenie lub patrzeć

Jak cienie układają się

Poprzez chłód dnia

Już wkrótce nawet imion

Tych, którzy zginęli, nikt nie będzie pamiętał

(Nazwisk takich jak Skrzypiński, Chmura

lub Antoni Milczarek).

Ich szorstkie głosy i rozdzierająca powaga

Już zgubiły się w wietrze.

Ale ich prawdziwe pomniki

Będą zawsze tam stać, w pyle

W szarych popiołach i stosach

Ułożonych ciał, nad którymi

Żadna modlitwa nie została nawet wyszeptana,

Żadna łza przelana przez zrozpaczoną matkę

Lub roztrzęsioną siostrę.

KATYN: THE 79th Anniversary of the Forest of Death

April 1940 is the month when many of the killings at Katyn Forest took place during World War II. Poles all over the world try to remember this every year, and I've been thinking about Katyn recently. I've been thinking about Katyn and my father.

When I was a child, he told me a lot of stories about what happened in the war, about things that happened to my mother's family and his family and to Poland. One of the stories that he came back to repeatedly was about what happened in the Katyn Forest near the Russian town of Smolensk in 1940.

He told me about how the Russians took 15,000-20,000 Polish Army officers and killed them. Nobody knows the number for certain.

My father used to say, "It's hard to count bones."

These soldiers were mainly reservists; that means they weren't professional soldiers, just civilian soldiers. In their daily lives, they were doctors and lawyers, teachers and priests. My father used to say that they were the future of Poland. He said that the Russians didn't want Poland to have a future, so they took these doctors and lawyers, scientists and librarians and tied them up and blindfolded them and shot them in the back of the head. They were buried in mass graves.

One of the things my dad also told me was that people knew about this, countries likes the US and England knew about this, and nobody did anything about it. The Russians, of course, denied it, and so did other countries. They didn't want to bring it up. I guess they figured what there was no point in talking about massacres and genocide.

.My father never forgot, and he never wanted me to forget about Katyn.

Years ago, I wrote a poem about Katyn for Echoes of Tattered Tongues, my book about my parents and their experiences in the war, and I want to share the poem with you on this 79th anniversary of the Katyn Massacre.

KATYN

There are no Great Walls there,

No towers leaning or not leaning

Declaring some king's success

Or mocking another's failure,

No gleaming cathedral where you can

Pray for forgiveness or watch

The cycle of shadows play

Through the coolness of the day,

And soon not even the names

Of those who died will be remembered

(Names like Skrzypinski, Chmura,

Or Antoni Milczarek).

Their harsh voices and tearing courage

Are already lost in the wind,

.

But their true monuments

Will always be there, in the dust

And the gray ashes and the mounds

Settling over the bodies over which

No prayers were ever whispered,

No tears shed by a grieving mother

Or a trembling sister.

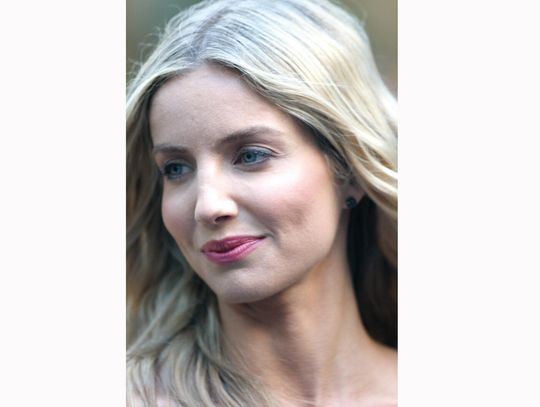

John Guzlowski

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera, za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem dwóch powieści kryminalnych o detektywie Hanku Purcellu oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Road of Bones”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.

—

John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.

fot.Radek Pietruszka/EPA/REX/Shutterstock

Reklama