Kochana mamo!

Wiem, że nie ma cię już od dawna, prawie od 15 lat, ale ostatniej nocy śniło mi się, że znów jestem z tobą.

To było w starym domu w Chicago, tym przy ulicy Potomac, pierwszym, którego numer pamiętam.

Sadziłaś kwiaty na trawniku za domem, gdzie nigdy kwiatów nie było, podlewałaś je wodą, która spadła z nieba. Kwiaty były czerwone, żółte i niebieskie; uwielbiałaś siadać na tarasie i patrzeć na nie.

Tą wodą myłaś też moje włosy. Powiedziałaś, że to zatrzyma moją młodość i pomoże mi wyrosnąć na wysokiego, kochającego i mądrego człowieka. Byłem zbyt mały, by zrozumieć, co te słowa naprawdę znaczą, ale wierzyłem ci.

Wreszcie przyszła jesień i spadł szary i ciężki deszcz, a potem śnieg, bardzo dużo śniegu, a ty włożyłaś śnieg do garnka, roztopiłaś go i umyłaś moje włosy.

Powiedziałaś, że woda ze śniegu jest tak samo czysta jak deszczówka.

Lata później w twoim domu w Arizonie, tym, którego numer ciągle pamiętam, umyłem twoje włosy w wodzie w umywalce. Nie protestowałaś. Rozumiałaś. Wiedziałaś, że na pustyni nie ma deszczu, ani tym bardziej śniegu.

Kiedy czekałaś, aż włosy wyschną, opowiadałaś mi historie, których nie mówiłaś nigdy przedtem. Opowiedziałaś mi o twojej siostrze, kiedy odwiedziła Lwów, o cukierku, który znalazła na siedzeniu w pociągu; o twojej śwince Karolinie i jak bardzo lubiłaś z nią siedzieć w lesie i patrze, jak opadają liście z drzew, gdy chłód zastępował długie lato. Opowiadałaś mi także o wojnie, o dniu, w którym Niemcy przyszli do twojego domu w lesie na zachód od Lwowa i zabili twoją matkę, siostrę i jej dziecko. Powiedziałaś mi też, że niemieccy żołnierze zrobili też inne rzeczy, o których nie możesz mi powiedzieć, mimo, że byłem dorosły i profesorem uniwersyteckim.

Słuchałem twoich historii, których nie słyszałem wcześniej i poznałem ciebie taką, jakiej nigdy nie znałem. I kiedy zapytałaś mnie znowu, skąd wziąłem wodę, to powiedziałem ci, że spadła z nieba.

A Letter to My Mother

Dear Mom,

I know you’ve been gone a long time now, almost 15 years, but I dreamt I was with you again last night.

It was in the old house in Chicago, the one on Potomac Avenue, the first one I remember the number for.

You planted flowers there in the backyard where there had never been flowers, watered them with the water that fell from the sky. The flowers were so red and yellow and blue that you loved to just sit on the porch and watch them.

You washed my hair with that water too. You said it would keep me young and help me grow tall and smart and loving. I was too young to know what all those words really meant, but I believed you.

Autumn came finally, and the rain fell grayer and harder, and then there was snow, so much snow, and you put the snow in a dishpan and melted it and washed my hair with it.

You said the water from snow was just as pure as the water from the rain.

Years later in your last house in Arizona, the one I still remember the number for, I washed your hair with water from the sink. You didn’t complain. You understood. You knew that there was no rain in the desert, no snow either.

While you waited for your hair to dry, you told me stories you never told me before. You told me about your sister and the time she visited Lvov, the candy she found on the seat of the train, about your pet pig Carolina and how much you loved just sitting with her in the forest and watching the leaves fall in the coolness that followed those long summers. You told me about the war too, about the day the Germans came to your home in the forest west of Lvov and killed your mother and your sister and your sister’s baby. You told me too that the German soldiers did other things that you still could not tell me about even though I was a grown man and a university professor.

I listened to your stories that I had never heard before and knew you like I had never known you, and when you asked me again where the water came from, I told you that I had collected it from the clouds.

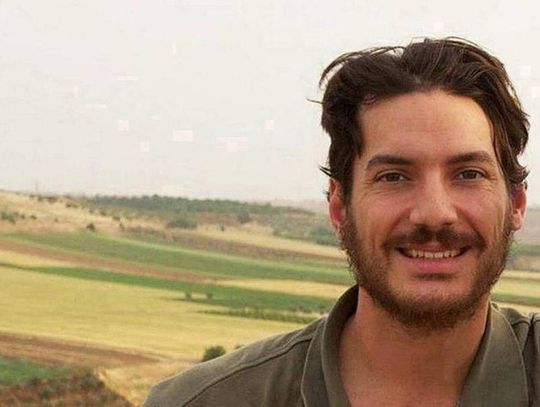

John Guzlowski

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera, za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem dwóch powieści kryminalnych o detektywie Hanku Purcellu oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Road of Bones”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.

—

John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.