Ta pandemia jest czymś, czego nigdy wcześniej nie doświadczyłem ani nie widziałem. Przeszedłem w swoim życiu przez obóz uchodźców, zamieć śnieżną, tornada, strach przed polio, huragany, ćwiczenia z bombą atomową, zamieszki rasowe, wydarzenia z 11 września 2001 roku, brak prądu, który trwał tygodniami oraz śmierć moich rodziców i przyjaciół. I nic z tego nie przygotowało mnie na to.

Przez ostatnie trzy tygodnie przechodzę samokwarantannę w moim domu w Lynchburgu w stanie Wirginia, z moją żoną, córką i wnuczką. Wszyscy czekamy aż to się skończy, ale tak naprawdę nie wiemy, czy skończy się w ogóle.

I co robimy podczas tego czekania?

Numer jeden to próba ignorowania tego, że mamy pandemię.

Próbujemy ignorować fakt, że restauracje w mieście są zamknięte i można zamawiać tylko na wynos; że zamknięte są parki, kościoły, szkoły, biblioteki i muzea, a liczba potwierdzonych przypadków koronawirusa rośnie tutaj i w całych Stanach Zjednoczonych o około 20 procent; ludzie umierają – tutaj i na całym świecie z powodu tego samego wirusa, którego nikt nie rozumie.

Staramy się ignorować fakt, że od trzech tygodni nie widzieliśmy naszych przyjaciół, że ludzie z którymi spotykaliśmy się co weekend, aby wspólnie żartować, napić się wina i porozmawiać, nagle są tak daleko, zamknięci.

Staramy się ignorować fakt, że jesteśmy sami.

Byłem już sam w przeszłości. W wieku 20 lat kochałem samotne wspinaczki i kemping. Pakowałem plecak i łapałem “stopa” przy autostradzie w kierunku dzikiej Montany lub Idaho, gdzie byłem sam przez tydzień lub dwa. Ale tamta samotność była niczym w porównaniu do tej teraz. Wiedziałem, że w tej dziczy są ze mną inni ludzie, i jeśli ta samotność stanie się zbyt wielka dla mnie, to wyjdę stąd, wystawię kciuk i złapię “stopa” do Chicago. Byłem sam, ale ta samotność była samotnością tymczasową. Bardzo łatwo mogłem tę samotność zakończyć. To była samotność, którą witałem w swoim życiu i której mogłem powiedzieć: „dość”.

Samotność, którą odczuwam w tej pandemii jest nie do porównania. To samotność otoczona tajemnicą, samotność w dziczy, z której nie mogę po prostu wyjść, kiedy mam już dość bycia samotnym.

Alone

This pandemic is like nothing I’ve ever experienced or seen before. I’ve lived through life in a refugee camp, blizzards, tornados, polio scares, hurricanes, atomic bomb drills, race riots, 9/11, blackouts that lasted for weeks, and the deaths of my parents and best friends. And none of that has prepared me for this.

For the last three weeks, I’ve been self-quarantined in my home here in Lynchburg, Virginia, with my wife and my daughter and my granddaughter. We’re all here waiting for something to end and not knowing really if it ever will.

And what do we do while we wait?

The number one thing is that we try to ignore that there is a pandemic.

We try to ignore the fact that the restaurants in town are closed except for curbside pickup, that the parks are closed or closing, that the churches and schools and libraries and museums are closed, that the number of confirmed cases of the coronavirus rises here and throughout the US by about 20%, that people are dying here and across the world from some kind of virus that no one has any understanding of.

We try to ignore the fact that we haven’t seen any of our friends in three weeks, that the people we used to get together with every weekend for some laughs and some wine and some talk are suddenly so far away in their own confinement.

We try to ignore the fact that we are alone.

I’ve been alone in the past. In my 20s, I loved to go hitchhiking and camping alone. I’d pack a backpack and stand on the side of a highway until I got a ride to some wilderness in Montana or Idaho where I would be alone for a week or two weeks, but that aloneness was nothing like this aloneness. I knew that there were other people in the wilderness with me, and I knew too that all I had to do if the aloneness got to be too much for me was walk out of the wilderness and stick my thumb out and catch a ride back home to my home in Chicago. I was alone, but the aloneness was an aloneness that was temporary. It was an aloneness I could put an end to pretty easily. It was an aloneness I welcomed into my life, and it was an aloneness I could say. “so long to.”

This aloneness that I’m feeling in this pandemic is nothing like that. It’s an aloneness surrounded by a mystery, an aloneness in a wilderness we can’t just walk out of when we get tired of being alone.

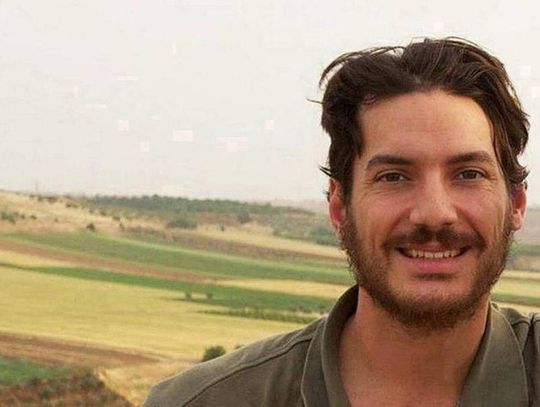

John Guzlowski

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera, za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem dwóch powieści kryminalnych o detektywie Hanku Purcellu oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Road of Bones”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.

—

John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.