Ostatnio oglądałem wiele doniesień z całego świata na temat tego, jak ludzie widzą historię i przeszłość. W Polsce Janusz Korwin-Mikke – były poseł, deputowany do Parlamentu Europejskiego – stwierdził, że pogromy Żydów w XIX i XX wieku były dobre dla ludności żydowskiej w Europie Wschodniej. Twierdzi on, że te pogromy odseparowały słabszych Żydów i zachęciły do rozwoju silniejszych. Powiedział, że w rzeczywistości wielu rabinów zachęcało do pogromów, ponieważ widzieli ich pozytywne efekty.

Czytałem także doniesienia o tym, jak Polska współpracowała z Niemcami w niszczeniu ludności żydowskiej w Polsce podczas wojny. Raporty te były szczególnie rozpowszechnione podczas ostatnich obchodów 75. rocznicy wyzwolenia Auschwitz.

Czytając te artykuły po raz kolejny zobaczyłem, jak skomplikowana jest historia, czasami nieuporządkowana i chaotyczna, i trudna do zrozumienia.

I czasami ludzie reagują na te trudności po prostu akceptując to, co powiedzieli im o historii inni ludzie, których lubią lub szanują.

Zakładam, że dlatego właśnie europoseł Korwin-Mikke powiedział o pogromach to, co powiedział. Jestem pewien, że nie powiedział tego dlatego, że akurat naprawdę wie coś o historii. Gdyby tak było, nie zapewniałby, że zabicie niektórych osób w społeczności jest dobre dla tej społeczności. To samo dotyczy tych, którzy twierdzą, że większość Polaków współpracowała z Niemcami w celu zniszczenia Żydów. Po prostu nie ma wiedzy na poparcie takiego twierdzenia.

Przez lata uczyłem literatury na uniwersytecie i często literatura, której nauczałem opierała się na historii. Czytaliśmy literaturę i czytaliśmy historię, na której się opierała. Podczas tych zajęć odkryłem, że wielu studentów koledżu nie miało zbyt dużej wiedzy na temat historii. A nawet nie chcieli jej mieć zbyt wiele. Chcieli tylko tyle, aby zaliczyć klasę, a czasami nawet tyle nie chcieli. Jak tylko usłyszeli, że będziemy opierać nasze studia literatury na historii, która stoi za tą literaturą, rezygnowali z zajęć. Szczególnie wtedy, gdy literatura, którą się zajmowaliśmy, dotyczyła ciemnych stron historii – wojny, ludobójstwa lub niewolnictwa. Studenci czasami pytali, czy romansem lub książką o miłości mogą zastąpić lekturę o Holokauście, ponieważ Holokaust był po prostu zbyt przygnębiający.

Czasami współczułem tym uczniom. Trudno jest zrozumieć historię ze względu na jej złożoność i ciemną stronę, ale trudno ją także zrozumieć, ponieważ powoli znika.

Co tak naprawdę możemy wiedzieć o naszej historii, jeśli większość z przeszłości już utraciliśmy? Moja matka znała historię bezpośrednio. Odczuwała ciężar śmierci swojej matki, swojej siostry i dziecka siostry z rąk nazistów. Ale co ja mogę wiedzieć o tych śmierciach?

Mogę tylko pamiętać przerażenie matki, kiedy opowiadała mi te historie, których nie mogła opowiedzieć bez załamania, odwracając ode mnie swoją zapłakaną twarz.

Więc co pozostało dla mnie do nauczenia się, co mogłem wiedzieć o żałobie i smutku mojej matki, o twarzy babci, do której strzelano raz za razem, o absolutnym smutku mojej cioci, która widziała swoje dziecko skopane na śmierć, i słyszała jego nieustający krzyk?

Nie ma zdjęć tego, co się wydarzyło, doniesień prasowych, naocznych świadków, a teraz nawet moja matka odeszła. Wszystko, co pozostało to garść połamanych wspomnień, które nigdy naprawdę do mnie nie należały.

To co można powiedzieć?

What’s Left to Say?

Recently, I’ve been following a number of news reports from around the world regarding how people view history, the past. In Poland recently, Janusz Korwin-Mikke, a member of the Polish parliament, apparently said that the pogroms directed at the Jews in the 19th and 20th century were good for the Jewish population of Eastern Europe. These programs -- he claims -- winnowed out the weak Jews and encouraged the development of strong Jews. He said that in fact many rabbis encouraged pogroms because they knew the positive effect they would have.

I’ve also been reading news reports about how Poland collaborated with the Germans in destroying the Jewish population of Poland during the war. These reports were especially prevalent during the recent commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

Reading such articles, I’m shown once again that history is complicated and sometimes messy and chaotic and difficult to make sense of.

And some people respond to this difficulty by simply accepting something they’ve been told about history by someone they respect or like.

I assume that’s why MP Janusz Korwin-Mikke would say what he said about pogroms. I’m sure it’s not because he actually knows anything about history. If he did, he wouldn’t be asserting that killing some people in a community is good for that community. The same is true of those who say that the majority of Poles collaborated with the Germans to destroy the Jews. There’s just no scholarship that supports such a claim.

For years I taught literature in a university, and often the literature I taught was based in history. We would read the literature and we would read the history the literature was based in. What I discovered teaching such courses was that many college students didn’t have much of a grasp on history. Nor did they want much. They wanted just enough to pass the class. And sometimes they didn’t even want that much. As soon as they heard that we would be basing our study of literature on history behind that literature, they would drop the course. I found this true especially if the literature we were studying dealt with the darker side of history, war or genocide or slavery. Students sometimes would ask if they could substitute a book about love or romance for a book about the Holocaust because the Holocaust was just too depressing.

Sometimes I sympathized with these students. History is hard to take in because of its complexity and its darker side, but it’s also hard to understand because it is slowly disappearing.

What can we really know about our history when so much of the past is already lost?

My mother knew history directly. She felt the weight of her mother's death and her sister's death and her sister's baby's death at the hands of the Nazis all her life, but what can I know of those deaths.

There was my mother's horror when she told me the stories, but my mother could not tell me much without breaking down, turning her face and its tears away from me.

And so what's left to learn, what can I know about my mother's grief, my grandmother's face when she was shot again and again, my aunt's absolute sorrow when she saw her baby daughter kicked to death, the baby's screams that would not stop?

There are no photographs of what happened, no news reports, no eye witnesses now that even my mother is gone, and all that's left is just a handful of broken memories that will never truly belong to me.

What's left to say?

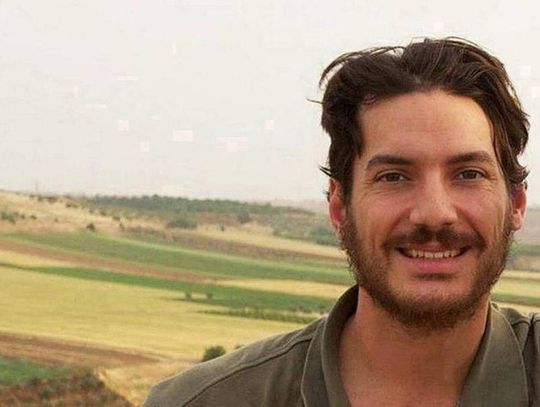

John Guzlowski

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera, za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem dwóch powieści kryminalnych o detektywie Hanku Purcellu oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Road of Bones”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.

—

John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.