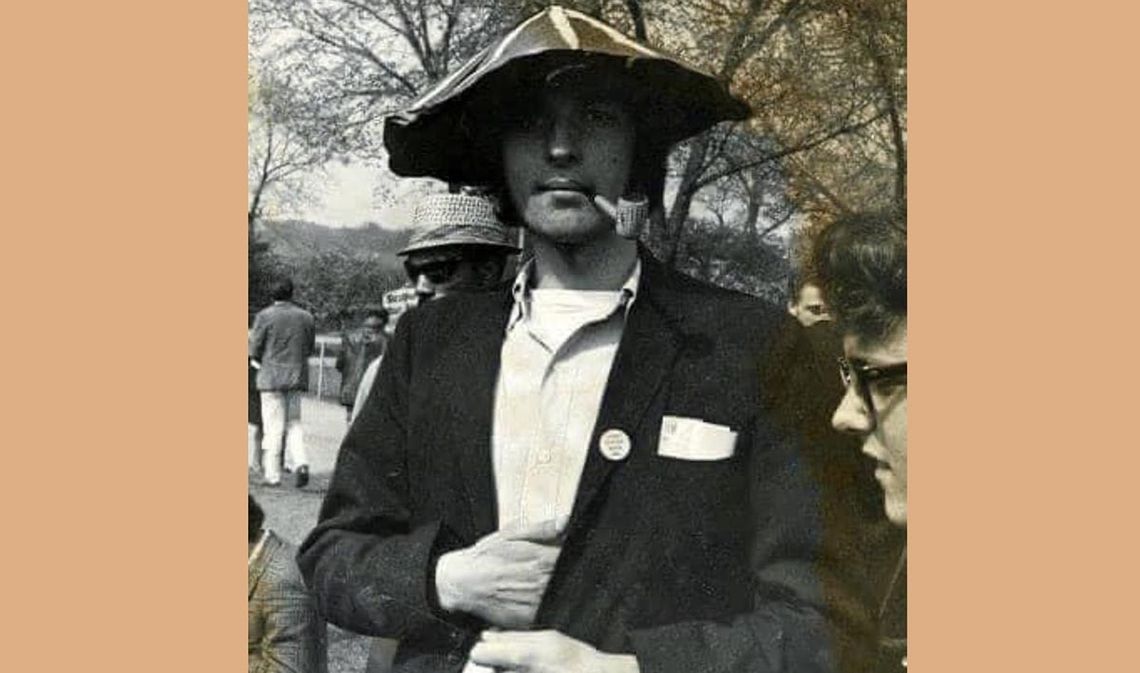

Na tym zdjęciu mam 21 lat i zrobiono je w Chicago, w Parku Granta. Stoję tam z kilkoma przyjaciółmi i czekamy na rozpoczęcie demonstracji antywojennej i zakończenie wojny w Wietnamie. Kiedy tak czekamy, aż nasi żołnierze przestaną zabijać partyzantów Vietcong, a partyzanci Vietcong przestaną zabijać naszych żołnierzy, to staramy się wyglądać na luzie. W ostateczności wyglądam na luzie w moim nón lá – kapeluszu wietnamskiego chłopa.

Wtedy odbywało się sporo tych antywojennych demonstracji. Było ich tak wiele, że teraz zlewają się ze sobą. Kiedy siadam i próbuję ustalić, kiedy zacząłem demonstrować i kiedy skończyłem, nie potrafię znaleźć żadnych konkretnych odpowiedzi. Od około 1966 do 1973 roku zawsze wydawało mi się, że idę na jakąś demonstrację w Chicago z moimi przyjaciółmi. Wiele z tych demonstracji wydaje się teraz małych – zebrana grupa kilkaset studentów, może tysiąc – ale wtedy wydawały się duże i ważne. Wszystko to zmieniła masakra w Kent State, kiedy Gwardia Narodowa zabiła czterech studentów. Demonstracje, które nastąpiły później, były większe niż wszystkie, które widziałem wcześniej. Liczba osób protestujących przeciwko tej wojnie wzrosła czterokrotnie niemal natychmiast i wydawała się zwiększać z każdą demonstracją.

Mój tata nie był jednym z tych protestujących przeciwko wojnie. W zasadzie on i ja zawsze kłóciliśmy się o wojnę. To były jedyne poważne kłótnie, jakie kiedykolwiek mieliśmy. W większości mój tata był dość wyluzowany i ja też, ale kłóciliśmy się o wojnę w Wietnamie. Był Polakiem, polskim patriotą, który nie mógł wrócić do Polski po wojnie, ponieważ czuł, że jego ojczyzna została przejęta przez rosyjskich komunistów. Bał się, że go zabiją, jeśli wróci – tak jak zabili brata mojej matki, gdy wrócił do Polski w 1945 roku.

Więc mój tata nie mógł zrozumieć, dlaczego miałbym wspierać komunistów przeciwko Amerykanom w Wietnamie. Dałem mu jakieś wyjaśnienie, że Viet Cong to demokratycznie wybrani przedstawiciele narodu wietnamskiego. Dużo czytałem o historii walki i myślałem, że znam odpowiedzi. Nie kupił tego i prawie pękło mu serce, gdy zobaczył, że ja, jego jedyny syn, staję po stronie gości, którzy zniewolili Polskę. To było dla nas kilka trudnych lat aż do zakończenia wojny.

Gdy teraz na to wszystko patrzę, uświadamiam sobie, że ludzie, którzy się kochają, mogą mieć zupełnie inne poglądy na wiele ważnych kwestii.

Ciągle jestem przeciwko wojnie, ale mam przyjaciół – dobrych przyjaciół i członków rodziny, którzy czują, że wojna w Ukrainie i ta w Strefie Gazy nie powinny się zakończyć, dopóki właściwi ludzie nie wygrają. Podobnie z politykami. Mam rodzinę i przyjaciół popierających Trumpa. Uważają, że Trump jest tutaj, aby uratować Amerykę przed szalonymi, lewicowymi, przebudzonymi idiotami, takimi jak ja, którzy popierali Bidena, a teraz popierają Kamalę Harris. I nie tylko wojna i polityka dzielą ludzi. Są też takie obawy, jak zmiana klimatu, kontrola broni, aborcja, podatki, niedroga opieka zdrowotna, nielegalna imigracja, bezrobocie, inflacja, traktowanie mniejszości przez system wymiaru sprawiedliwości i tak dalej.

Lista rzeczy które nas dzielą wydaje się rosnąć i rosnąć, ale moje kłótnie na temat wojny w Wietnamie z moim ojcem nauczyły mnie, że osoba, którą kochasz, jest nadal tą samą osobą, którą kochasz, i nigdy nie chcesz oddalać się od osoby, którą kochasz, która odwzajemnia twoje uczucie – bez względu na to, w jakiej sprawie lub sprawach się z nią nie zgadzasz.

Ta miłość jest ważniejsza niż cokolwiek innego.

A Photo of Me from 1969

I’m 21 in the picture here, and it was taken in Chicago’s Grant Park. I’m standing around with some friends waiting for an anti-war demonstration to begin and the Vietnam War to end. While we wait for our soldiers to stop killing the Viet Cong and for the Viet Cong to stop killing our soldiers, we are trying to look cool. At least I was cool in my nón lá, my Vietnamese peasant hat.

There were a lot of these anti-war demonstrations back then. There were so many that they now seem to blend into each other. When I sit down and try to figure out when I started to demonstrate and when I finished, I can’t come up with any solid answers. From about 1966 to 1973, I always seemed to be going to some demonstration in Chicago with my friends. A lot of these demonstrations seem small now, a couple hundred students gathered together, maybe a thousand, but they seemed big back then and important. What changed all that was the Kent State Massacre when the National Guard killed four students. The demonstrations that followed were bigger than any I had seen beforehand. The number of people protesting that war quadrupled almost instantly and seemed to increase in size with every demonstration.

My dad wasn’t one of the war protesters. In fact, he and I were always arguing about the war. They were the only serious arguments that we ever had. For the most part, my dad was pretty easy going and so was I, but we fought over the Vietnam War. He was a Pole, a Polish patriot, who couldn’t go back to Poland after the war because he felt his homeland had been taken over by the Russian Communists. He was afraid that they would kill him if he went back like they killed my mother’s brother when he returned to Poland in 1945.

So my dad couldn’t see why I would be supporting the Communists against the Americans in Vietnam. I gave him some kind of explanation about the Viet Cong being the democratically chosen representatives of the Vietnamese people. I was doing a lot of reading about the history of the struggle, and I thought I had the answers. He didn’t buy it, and it almost broke his heart to see me, his only son, siding with the guys who had enslaved Poland. It was a rocky few years for us until the war ended.

Looking back on all this now, one of the things I realize is that people who love each other can have totally different views on a lot of important issues.

I’m still anti-war, but I have friends, good friends, and family members who feel the war in Ukraine and the one in Gaza shouldn’t stop until the right people win. The same thing with politics. I have family and friends who are pro-Trump. They feel that Trump is here to save America from the crazy, left-wing, woke idiots like me who supported Biden and now support Kamala Harris. And it’s not just war and politics that separate people. There are also concerns like climate change, gun control, abortion, taxes, affordable health care, illegal immigration, unemployment, inflation, the criminal justice system’s treatment of minorities, and on and on.

The list of things that separate us seem to grow and grow, but what my arguments about the Vietnam War with my dad taught me is that the person you love is still the person you love, and you never want to separate yourself from the person you love who loves you back – no matter what thing or things you disagree with them about.

That love is more important than anything.

John Guzlowski

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem serii powieści kryminalnych o Hanku i Marvinie, których akcja toczy się w Chicago oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Retreat— A Love Story”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.-John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.