Od długiego już czasu wysłuchuję osób wysiedlonych i ich historii. Prawdopodobnie pierwszą, którą usłyszałem, była ta mojej mamy, kiedy wsiadaliśmy z pokładu amerykańskiego statku „Generał Taylor”, którym przewożono przesiedleńców z Niemiec do USA po drugiej wojnie światowej. Moja mama zaczęła opowiadać tę historię, kiedy zniknął mój ojciec. Zniknął, gdy schodziliśmy z pokładu, a jego nieobecność mnie przestraszyła. Moja mama powiedziała, żebym się nie martwił, że on ciągle włóczy się dookoła, poszukując tajemniczych rzeczy, których nikt nie chce, jeśli je znajdzie. I uśmiechnęła się i powiedziała, że tak ją po raz pierwszy znalazł w obozie pracy niewolniczej w Niemczech.

Te opowieści przesiedlonych nie skończyły się, kiedy moja rodzina znalazła dom w Chicago. Jedną z rzeczy, którą w sobotnie wieczory lubili robić moi rodzice i ich przyjaciele imigranci, było siadanie przy stole z drinkiem i opowiadanie o tym, jak złamała ich wojna i jak cierpieli, by się po niej pozbierać; opowieści o przyjaciołach, których utracili i tych, których znaleźli w czasie wojny, opowieści o tym, co kochają w Ameryce i do czego nie mogą się przyzwyczaić.

Słuchanie tych historii nie skończyło się, kiedy dorosłem, wyprowadziłem się od rodziców i rozpocząłem swoje własne życie.

Ciągle słyszę te historie o doświadczeniu polskich przesiedleńców, ale teraz słyszę je w książkach. Słyszę je w książce Donny Urbikas „My Sister’s Mother” i Anthony Bukoskiego „Polonaise: Stories” i Kathryn Hulme „The Wild Place” i w wielu innych książkach.

Jednakże tym, czego nie słyszę często, są doświadczenia polskich przesiedleńców i imigrantów, którzy po wojnie zostali przesiedleni do innych krajów.

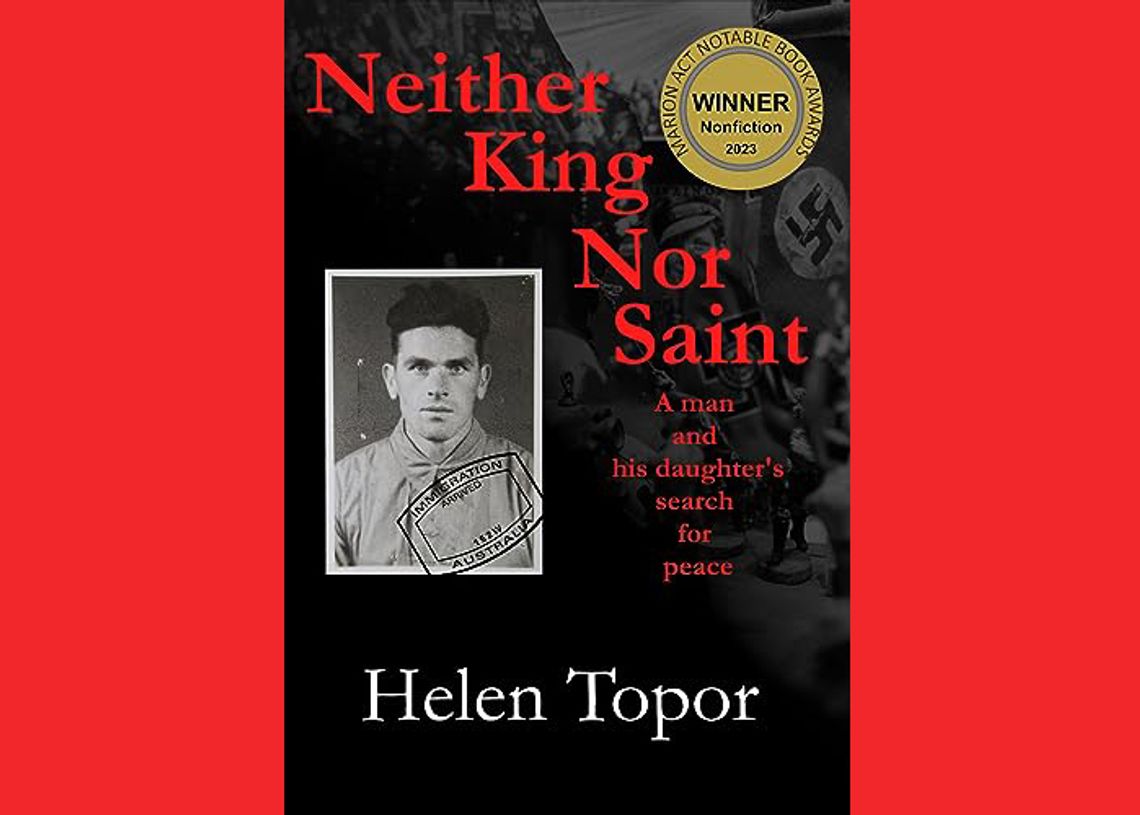

Książka-wspomnienia Helen Topor „Neither Saint nor King: A man and his daughter’s search for peace” zmieniła wszystko. Wiele mnie nauczyła o życiu przesiedleńców, którzy zostali wysłani po wojnie do Australii.

Jej książka skupia się na życiu jej rodziny, od chwili, gdy jej ojciec zostaje zabrany do Niemiec jako robotnik przymusowy na początku wojny, przez życie rodziny w obozie dla przesiedleńców w Niemczech, aż po lata, kiedy jej rodzina żyje w wadliwym systemie australijskiego rządu, który nie radzi sobie z przesiedleniami osób repatriowanych.

Ostatnie lata, te spędzone w Australii, są najbardziej niepokojące.

Kiedy wspominam swoje własne życie, jako osoby przesiedlonej w Ameryce, wydaje mi się ono ciężkie i trudne, ale w niczym nie przypomina życia, jakie rodzina Helen Topor zmuszona była prowadzić przez prawie dwie dekady.

Po przybyciu do Australii po niemal 5 latach spędzonych w obozie dla przesiedleńców w Niemczech, rodzina Heleny Topor została natychmiast rozdzielona przez australijskich urzędników. Jej ojciec został wysłany do pracy w jednym regionie kraju, a żona i dwójka dzieci zostały zakwaterowane w ośrodku dla przesiedleńców w innym regionie. Jej ojciec miał wrażenie, że on i jego rodzina byli traktowani w podobny sposób, w jaki on był traktowany jako robotnik przymusowy, a później przesiedleniec w Niemczech. Miał wrażenie, że nieustannie postrzega się ich jako untermensch – podludzi, tak samo jak w Niemczech.

Jedną z najważniejszych cech tych wspomnień jest dla mnie otwartość Helen Topor na temat psychologicznych skutków, jakie przesiedlenie wywarło na jej rodzinę. Zanim został zabrany przez Niemców, jej ojciec czuł się człowiekiem, któremu uda się spełnić wszystko, o co poprosi go życie. Miał umiejętności, których potrzebował świat. Zniewolenie przez Niemców i złe traktowanie przez Australijczyków zniszczyło tę pewność siebie, złamało go. Jego życie w Australii stało się życiem pełnym porażek, alkoholizmu, depresji i udręki, a te problemy psychiczne wpłynęły na jego żonę i trójkę dzieci w sposób, z którym musieli się uporać przez całe życie.

Nie mogę powiedzieć, że moi rodzice lub osoby przesiedlone, które znałem, cierpiały w systemie tak represyjnym jak ten ustanowiony przez Australijczyków, ale mogę powiedzieć, że widziałem też te problemy psychologiczne, jakich doświadczyła Helen Topor ze swoją rodziną. Jej chęć napisania o tym i porozmawiania o latach, jakie zajęło choć częściowe rozwiązanie tych problemów, mówi mi, że jest to książka, którą powinien przeczytać każdy zainteresowany doświadczeniami polskich osób przesiedlonych i imigrantów.

Neither Saint nor King

I’ve been listening to DPs (Displaced Persons) and their stories for a long time. Probably, the first one I heard was from my mom when we climbed off the General Taylor, an American ship used to transport DPs from Germany to the US after World War II. What started my mother telling the story was my father’s disappearance. He had vanished as we were disembarking and his absence frightened me. My mom told me not to worry. She said he was always wandering around, looking for mysterious things no one would want if he found them, and she smiled and said that was how he first found her in a slave labor camp in Germany.

And these DP stories didn’t stop when my family finally found a home in Chicago. One of the things my parents and their immigrant friends loved to do on a Saturday night was sit around the table with a drink and tell stories about how the war broke them and how they struggled to put themselves together, stories about the friends they lost and the friends they found in the war, stories about what they loved about America and what they couldn’t stand.

And hearing such stories didn’t stop when I grew up and moved away from my parents and started my own life.

I still hear these stories about the Polish DP experience, but now I hear them in books. I hear them in Donna Urbikas’s My Sister’s Mother and Anthony Bukoski’s Polonaise: Stories and Kathryn Hulme’s The Wild Place and so many more books.

However, what I don’t often read about are the experience of Polish DPs and immigrants who repatriated to other countries after the war.

Helen Topor’s memoir Neither Saint nor King: A man and his daughter’s search for peace changed all that. It taught me so much about the lives of DPs who were shipped to Australia after the war.

Her book focuses on her family’s life from the time her father is taken to Germany as a slave laborer early in the war to the family’s life in a Displaced Person’s camp in Germany to the family’s years of living under the Australian government’s flawed system for dealing with the DPs who were repatriated there.

The last part, those years in Australia, is the most disturbing.

When I think of my own life as a DP in America, I think of it as being hard and difficult, but it is nothing like the kind of life Helen Topor’s family was forced to live for almost two decades.

Arriving in Australia after almost 5 years in the DP camps in Germany, Helen Topor’s family was immediately broken up by the Australian repatriation authorities. Her father was sent to work in one area of the country and his wife and two children were housed in a DP settlement in another. Her father felt like he and his family were being treated much the same way he was treated as a slave laborer and later a DP in Germany. He felt they were being seen constantly as untermensch, subhumans, just as they had been in Germany

One of the most important features of this memoir for me is Helen Topor’s openness about the psychological effects being DPs had on her family. Before being taken by the Germans, her father felt like a man who could succeed at anything his life asked of him. He had skills that the world needed. His enslavement by the Germans and his mistreatment by the Australians destroyed that confidence, broke him. His life in Australia became a life of failure and alcoholism and depression and anguish, and these psychological problems impacted his wife and his three children in ways they struggled a lifetime to heal.

I can’t say that my parents or the DPs I knew suffered under a system as repressive as the one established by the Australians, but I can say that I also saw the types of psychological problems that Helen Topor experienced in her family. Her willingness to write about it and talk about the years that it took to even partially resolve these problems tells me that this is a book everyone interested in the experience of Polish DPs and immigrants should read.

John Guzlowski

amerykański pisarz i poeta polskiego pochodzenia. Publikował w wielu pismach literackich, zarówno w USA, jak i za granicą, m.in. w „Writer’s Almanac”, „Akcent”, „Ontario Review” i „North American Review”. Jego wiersze i eseje opisujące przeżycia jego rodziców – robotników przymusowych w nazistowskich Niemczech oraz uchodźców wojennych, którzy emigrowali do Chicago – ukazały się we wspomnieniowym tomie pt. „Echoes of Tattered Tongues”. W 2017 roku książka ta zdobyła nagrodę poetycką im. Benjamina Franklina oraz nagrodę literacką Erica Hoffera za najbardziej prowokującą do myślenia książkę roku. Jest również autorem serii powieści kryminalnych o Hanku i Marvinie, których akcja toczy się w Chicago oraz powieści wojennej pt. „Retreat— A Love Story”. John Guzlowski jest emerytowanym profesorem Eastern Illinois University.

-

John Guzlowski's writing has been featured in Garrison Keillor’s Writer’s Almanac, Akcent, Ontario Review, North American Review, and other journals here and abroad. His poems and personal essays about his Polish parents’ experiences as slave laborers in Nazi Germany and refugees in Chicago appear in his memoir Echoes of Tattered Tongues. Echoes received the 2017 Benjamin Franklin Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Foundation's Montaigne Award for most thought-provoking book of the year. He is also the author of two Hank Purcell mysteries and the war novel Road of Bones. Guzlowski is a Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University.